In 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took the steps and uttered the words that etched forever into history what it was like for human beings to touch land not of the Earth. But it was the third astronaut in their crew—the one who had remained in orbit above the moon—who saw what the Scottish poet Dylan Thomas conjured only in the vivid imagery of words when he wrote I think that if I touched the earth / it would crumble / it is so sad and beautiful / so tremulously like a dream.

“The thing that really surprised me,” Michael Collins said, reflecting on the experience of looking back at the Earth, glowing and indivisible against the endless expanse of space, “was that it projected an air of fragility…I had a feeling it’s tiny, it’s shiny, it’s beautiful, it’s home, and it’s fragile.”

Maintaining the Value of Your Real Estate in the Post-Pandemic World

The first images of the Earth taken from space—the “Overview Effect,” as is was later termed—coincided with the beginnings and the rise of the environmental movement, particularly Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund, Barbara Belvisi notes. From the plant-filled, ground floor office in Paris’s 13th arrondissement, Belvisi, the 36-year-old founder and CEO of Interstellar Lab, deals with a bit of the Earth’s fragility every day: she and her team are working to figure out how we might eventually grow our planet’s flowers, trees, food, on the moon and Mars. And she fully intends for the technology they’re developing to serve a purpose down here, as well as way out in space.

Enamored with science fiction as a kid (she ticks off the names of the writers who made her dream of the day humanity would become interplanetary, like Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and Réné Barjavel, the French sci-fi writer who first presented the “Grandfather Paradox,” and whose work often dealt with the environmental legacy that would be left to future generations) Belvisi spent her early career in finance and venture capital. Initially, her venture capital work centered on investing in robotics startups before she launched Interstellar Lab in 2018. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the shift in career focus happened to coincide with Interstellar overtaking iRobot as her favorite movie.

“I realized that the companies she was backing were impressive, but not necessarily offering solutions to some of the biggest challenges we face,” Belvisi says. “So I decided I wanted to build something that is really going to help the planet—food production, water, waste management…and that was around the same time the boosters from SpaceX first came back to Earth, and so I made the connection between the technology and the systems we will need to live on the moon and down the road on Mars, and the technology we need on Earth.”

After teaching herself the basics of architecture and aeroponics (there are brilliant people who make you feel out of your depth when talking to them, and brilliant people who make you feel smarter—Belvisi is the latter), she faced down initial skepticism, and eventually talking her way into a 9-month guest desk at Nasa’s Ames Space Portal.

“At the beginning, it was hard in France because people didn’t want to believe I could go outside of my ‘zone’ [of finance], and especially when you’re a woman it’s even worse—when I started explaining what I wanted to do everybody was looking at me like I was crazy,” Belvisi says. “But when I went to Los Angeles and San Fransisco, everybody was like, ‘oh my God, this is awesome.’”

From SciFi to Business

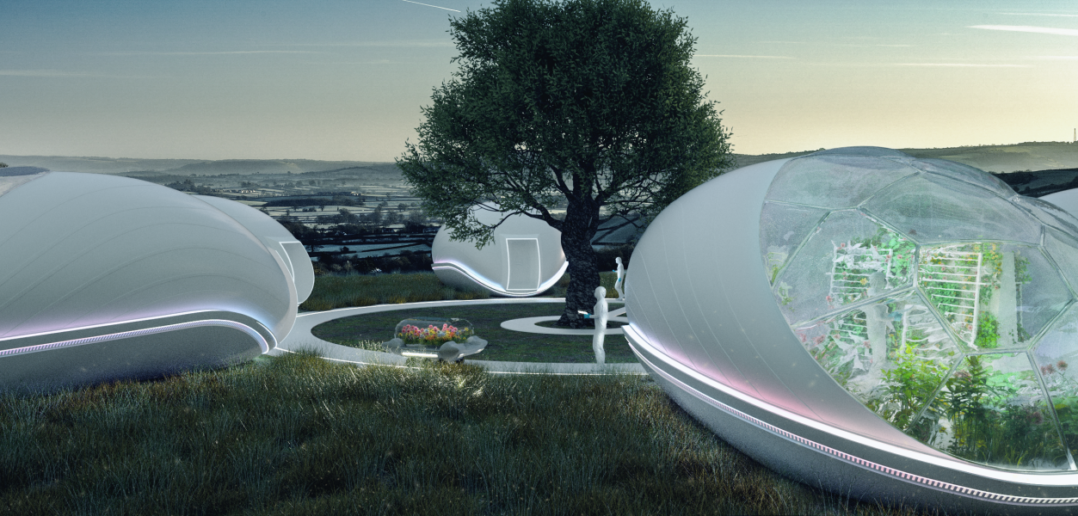

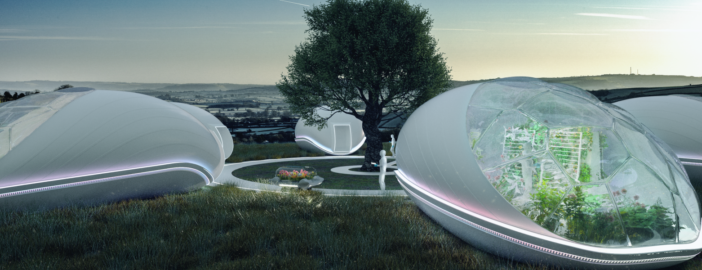

Here’s how the “BioPods” work: made of an inflatable membrane on a composite base, they are elliptical instead of circular, in order to maximize the balance between structural strength and interior space. The first full size prototypes (currently under construction in Germany and is expected in the fall) are meant to test how well the BioPods can control atmospheric conditions internally as well as the materials used to build them (a combination of ETFE, Aerogel, and PTFE). But the versions that will eventually be deployed on the moon, or Mars, will use a 50-centimeter layer of water as protection against radiation. The company just recently partnered with French 3D printing startup Soliquid to produce the BioPods’ inflatable membranes. (Interstellar Lab is not yet making an orbital version, because, according to Belvisi, zero gravity farming is a completely different undertaking.)

“The most important thing when you go to space is to have a system that is very easy to deploy—you don’t want to dig holes on the moon, you don’t want to have any foundation— very light but also very resistant, and we want to be able to connect the domes together,” Belvisi explains.

In their leaf-like shape and ability to connect to each other, the pods reveal a certain biomimicry; indeed, Interstellar Lab envisions them fitting together and growing the way a plant might. Eventually Belvisi and her team will design habitations, but for now the focus is squarely on agriculture—for food consumption, but also plants for “accompaniment,” one of the lessons drawn from the lockdowns the team had to live through during the pandemic.

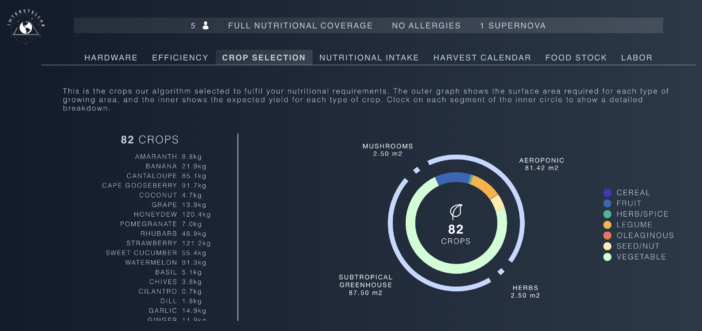

In order to figure out which plants grow well, under what conditions, what to pair together, and how much food can be produced, Interstellar Lab has a sophisticated model built on 55 stoichiometric equations enabling it to calculate the composition of the atmosphere inside a closed bipod given the interactions and reactions of different gases and elements with each other. “We started with the modeling, we added a lot of algorithms and from that we can predict what’s going to happen and size the hardware, so you know how big and what volume the CO2 scrubber needs to be, how much water you need and how big the water tanks will be, and from there you can design the shell,” Belvisi explains.

A beta version of the software is available online, where you can input the number of ‘settlers’ that need to be fed, as well as determine specifics about their diet, and see how many BioPods would be needed to support them, and even what an overview of a year’s worth of harvests might look like. For a basic 5 person mission requiring full nutritional coverage, the simulator told me I would need one BioPod, with 190 square meters of internal space, which would produce roughly 5,700 kg of food per year, using just 38m3 of water—what traditional agriculture would require 46,000m2 and 2500m3 of water to do.

Behind the office’s enormous windows that look onto the banks of the Seine, there are dozens of plant species growing in a myriad of differently shaped aeroponics structures. Vegetables like cucumber and squash do particularly well, Belvisi says.

If doing science fiction in real life is one thing, operating a business is another. “Relying on how many modules you’re going to sell into space [for astronauts]to live is not a sustainable business model,” Belvisi admits. Luckily for Interstellar Lab, which nevertheless has contracts with both Nasa and the European Space Agency, they’ve found interest from an unlikely economic sector: cosmetics, which consumes huge quantities of niche plants—everything from jasmine, to vanilla, to roses.

Because the BioPods are able to accurately recreate specific microclimates (“we can recreate Madagascar’s ecosystem, for growing Bourbon vanilla,” says Belvisi) they could be used to grow and supply these niche ingredients that major cosmetics brands use in large quantities in a more sustainable and localized way than production that takes up thousands of hectares in tropical regions, and also consumes less water. “There’s an ethical question [for these companies],” Belvisi says. “Every year, because of climate change, there’s a plant that’s not growing anymore, and also there is a lot of land going to produce flowers for luxury cosmetics instead of producing food, and it’s going to get worse.”

Could her BioPods eventually find even more uses on earth—in adapting full scale agriculture to climate change in severely affected regions, or even in housing future waves of climate refugees? “This is unfortunately where we seem to be going,” Belvisi laments, though they aren’t planning to start work on habitation and waste-to-energy until much of the testing with the initial BioPods has been completed.

Maintaining the Value of Your Real Estate in the Post-Pandemic World

“Our goal is really to be one of the first players to put a greenhouse on the moon,” Belvisi says, as part of Nasa’a Artemis Program to return to the lunar surface. “If humans can carry life to other planets, it’s really beautiful—I think it’s very powerful as well.” And she plans to be there to see it. When I ask her if she if she would, herself, go to the surface of the moon or Mars Belvisi answers without hesitation, “One hundred percent.”