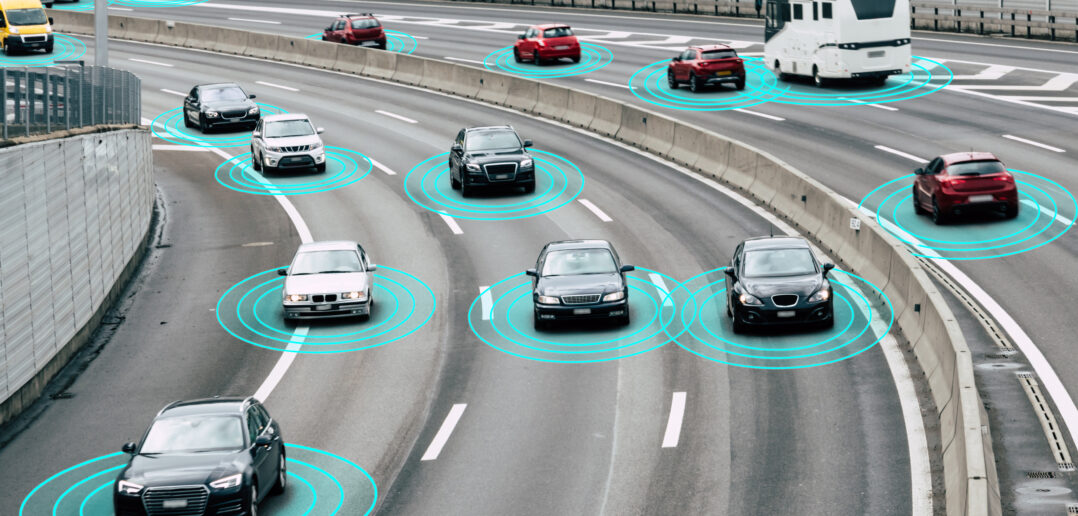

Automated vehicles (AV) are coming, and they can make our lives significantly better, take Grandma to the Doctor, drop off the kids at school, allow you to work safely or play or sleep while in the car. But they also have the potential to make our lives significantly worse. As a recent paper by Adam Millard-Ball of UC Santa Cruz points out, self-driving cars have the potential to wreak havoc on traffic.[1] Millard-Ball uses a microsimulation model to show that left unchecked, automated cars will have little to no incentive to park, and will instead simply cruise, adding to already congested streets.

Millard-Ball’s paper suggests as little as 15% of vehicles would need to cruise for parking to create grid lock. This makes sense for three reasons. The first is that most cars in the future will be running so efficiently or on batteries that fuel costs are not a consideration as they are today. The second factor is that busy professionals want access to their cars quickly and why park a vehicle when it can circle an area, what Norm Miller called “hover mode” in earlier papers and talks.[2] A third factor for Uber and Lyft style vehicles is that it might save on parking costs.

“Congestion pricing has long been a holy grail of urban policy, but political and technological considerations have hampered its widespread use beyond a small number of cities.”

Millard-Ballard does offer a reasonable solution though: Congestion Pricing, just as they have had in Singapore for decades. “Congestion pricing has long been a holy grail of urban policy, but political and technological considerations have hampered its widespread use beyond a small number of cities,” suggests the paper. Congestion pricing as applied in Singapore requires a toll be paid by any car entering the most congested parts of a city. Cars wishing to enter this zone must purchase a toll box, similar to those used on automated toll roads for access. When cars enter these zones, the car owner is automatically notified and charged. Singapore’s system uses predictive analytics to set prices based on the congestion at different times.[3] By some estimates, this has reduced traffic in Singapore by as much as 45% with associated environmental benefits[4].

Why does congestion pricing work?

Perhaps a comparison will help. Traffic is a bit like second hand smoke. Both are what economists refer to as “externalities.” An externality is a cost or benefit that affects a party who did not choose to incur the cost or benefit. In the case of second hand smoke, the bystander receives the negative health effects of the smoke, without incurring the benefits, whatever they are for smokers. Externalities can be positive or negative. It’s nice to be near an airport but the noise is a negative externality.

How do societies typically deal with negative externalities?

Usually via some form or regulation, taxes, or subsidies. We already pay gas taxes intended for road maintenance, but we don’t all cause the same harm to the roads based on vehicle size and how much we drive. Congestion pricing is like a type of user tax that tries to base that tax on the actual use of the road and the negative externality imposed on others. Without a congestion tax on autonomous vehicles, you could be someday sitting in a mass of driverless cars slowing into gridlock, or worse, trying to enter a stream of cars with your signal on and a polite smile while the AVs run past you without noticing as they were trained on New York City taxi driver rules.

Why does congestion pricing work?

Because it uses market principles to allocate resources. During your next traffic jam please look at the cars in front of you, and think about how much you would pay to remove some of them.

With modern technology, we can improve on Singapore’s system and congestion pricing and make it even better. AI Cameras, sensors and cameras on corners could photograph and monitor cars entering urban zones. Transponders could be required on all new cars starting in a few years as another way to track all vehicles.

Alternatively, your smartphone may have an apps tied to your license plate or vehicle, which would reduce the need for the creation or purchase of new hardware. Such tolls could vary by time of day and be zero in some hours and escalate as rush hours peak. A warning display could tell a driver if they are approaching such a zone and cars entering the zone without a toll box would be subject to fines. An alternative or complement to zones, and something we already have in the United States are toll lanes. This may be an even better approach, as it allows for a more politically and socially palatable alternative to implementation. One or two toll lanes may be more acceptable to the public. We must also consider that many people will be opposed to congestion pricing, and view it as a new tax, or socially inequitable. We propose the terms: “airport lanes” or “late lanes.” Most of the general public can relate to being late for an airplane, or an important appointment. Stuck in bumper to bumper traffic, desperately looking at the clock, many people would gladly pay a few dollars to get into a lane that was moving freely. We can shift the perception from this being a new tax, to a new amenity.

Why consider such a congestion toll plan or “Late lanes” on automated vehicles now?

Autonomous vehicles are not yet here, so the industry of private AV transport companies which will exist, will not be lobbying politicians to vote against such a congestion pricing plan. In fact, the proposal could be such that it ONLY applies to driverless AVs at first, affecting no one currently driving their own vehicle. This makes it almost impossible to oppose in 2019. Later, as more AVs crowd the urban streets, such tolls can be applied to all vehicles. Today, the environmentalists are likely to support any plan that will lower emissions, and businesses are likely to support a plan that lets traffic flow more efficiently. Smart cities will plan ahead and consider a congestion toll sooner than later on driverless AVs before they are actually here.

[1] See in 2019

[2] See https://irei.com/publications/article/autonomous-vehicles-work-implications-real-estate/ in 2017.

This post was co-authored by Morgan Plaster, an MSRE from the University of San Diego and an MBA student. During the housing bust, Morgan Plaster worked as a housing analyst, and is used to explaining things to people who are paid to not understand it.

This post was co-authored by Morgan Plaster, an MSRE from the University of San Diego and an MBA student. During the housing bust, Morgan Plaster worked as a housing analyst, and is used to explaining things to people who are paid to not understand it.