Most of the current blockchain real estate startups are embarrassingly bad. I’ve been actively involved in blockchain real estate since 2013 and I’m shocked at the garbage being funded, developed, and written about. This is not what I envisioned where we would be in 2018. Companies like ChromaWay and a few others are solid. The rest, a mess.

While blockchain offers great solutions to the property industry, the current implementations in real estate fail to achieve that promise because most startups are doing initial coin offerings (ICOs).

Using blockchain to crowdfund open source software has promise. But as Joi Ito wrote,

The initial idea was a pretty good one — blockchain technology could be used to issue new cryptographically secure “tokens” or “coins” that are easy to transmit peer-to-peer. The coins could be sold to fund open-source software projects and other services that people find useful but are hard to finance with traditional structures. They could even function as shares and thus allow startups to finance themselves far more efficiently, from a broader range of people, and without the intermediaries that take fees and require a drawn-out process. Or the “coins” could represent some unit of utility, such as a gigabyte of storage or access to a network…

My concern with today’s ICOs is that they’re being fueled by the gold-rush mentality around cryptocurrencies, and so are deployed in irresponsible ways that are causing harm to individuals and damaging the ecosystem of developers and organizations. We haven’t set up the legal, technical, or normative controls yet, and many people are taking advantage of this.¹

Before I discuss two better ways to do crowdfunding for startups, I will first discuss the problems with ICOs.

The dynamics and incentives of ICOs undermine blockchain’s potential for real estate for ten reasons.

1) Token Focus

With ICOs, business plans are optimized to raise the maximum amount of capital upfront, quickly, rather than to create a sustainable business model over the long term that solves a real problem. The entrepreneurs spend more energy and time on financially engineering their token than software application engineering. As a result, the investors invest based on the economics and upside potential of the coin, independent of the quality and utility of the proposed software application that the coin is supposed to fund.

The focus on a token that rises in value also creates legal problems. In December, the SEC shut down the $15 million Munchee ICO for various violations, including:

In the MUN White Paper, on the Munchee Website and elsewhere, Munchee and its agents further emphasized that the company would run its business in ways that would cause MUN tokens to rise in value. First, Munchee described a ‘tier’ plan in which the amount it would pay for a Munchee App review would depend on the amount of the author’s holdings of MUN tokens. For example, a “Diamond Level” holder having at least 300 MUN tokens would be paid more for a review than a “Gold Level” holder having only 200 MUN tokens. Also, Munchee said it could or would “burn” MUN tokens in the future when restaurants pay for advertising with MUN tokens, thereby taking MUN tokens out of circulation,” wrote the SEC.

The final nail?

Munchee published a blog post on October 30, 2017 that was titled “7 Reasons You Need To Join The Munchee Token Generation Event.” Reason 4 listed on the post was “As more users get on the platform, the more valuable your MUN tokens will become” and then went on to describe how MUN purchasers could “watch their value increase over time” and could count on the “burning” of MUN tokens to raise the value of remaining MUN tokens.²

2) Scams

The ability to quickly raise a large sum of money attracts charlatans and scammers who often lack deep real estate experience or sophisticated blockchain software engineering experience, or both. The first criminal charges brought by the SEC for an ICO was a real estate project called REcoin:

The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged a businessman and two companies with defrauding investors in a pair of so-called initial coin offerings (ICOs) purportedly backed by investments in real estate and diamonds.

The SEC alleges that Maksim Zaslavskiy and his companies have been selling unregistered securities, and the digital tokens or coins being peddled don’t really exist. According to the SEC’s complaint, investors in REcoin Group Foundation and DRC World (also known as Diamond Reserve Club) have been told they can expect sizeable returns from the companies’ operations when neither has any real operations.

Zaslavskiy allegedly touted REcoin as “The First Ever Cryptocurrency Backed by Real Estate.” Alleged misstatements to REcoin investors included that the company had a “team of lawyers, professionals, brokers, and accountants” that would invest REcoin’s ICO proceeds into real estate when in fact none had been hired or even consulted. Zaslavskiy and REcoin allegedly misrepresented they had raised between $2 million and $4 million from investors when the actual amount is approximately $300,000.³

3) False Promises

To garner hype, entrepreneurs promise to unrealistically “do it all” rather than realistically focus on solving just one problem. They use words like “comprehensive platform” and “End-to-end solution” and throw everything in their white paper. For example, BitRent⁴:

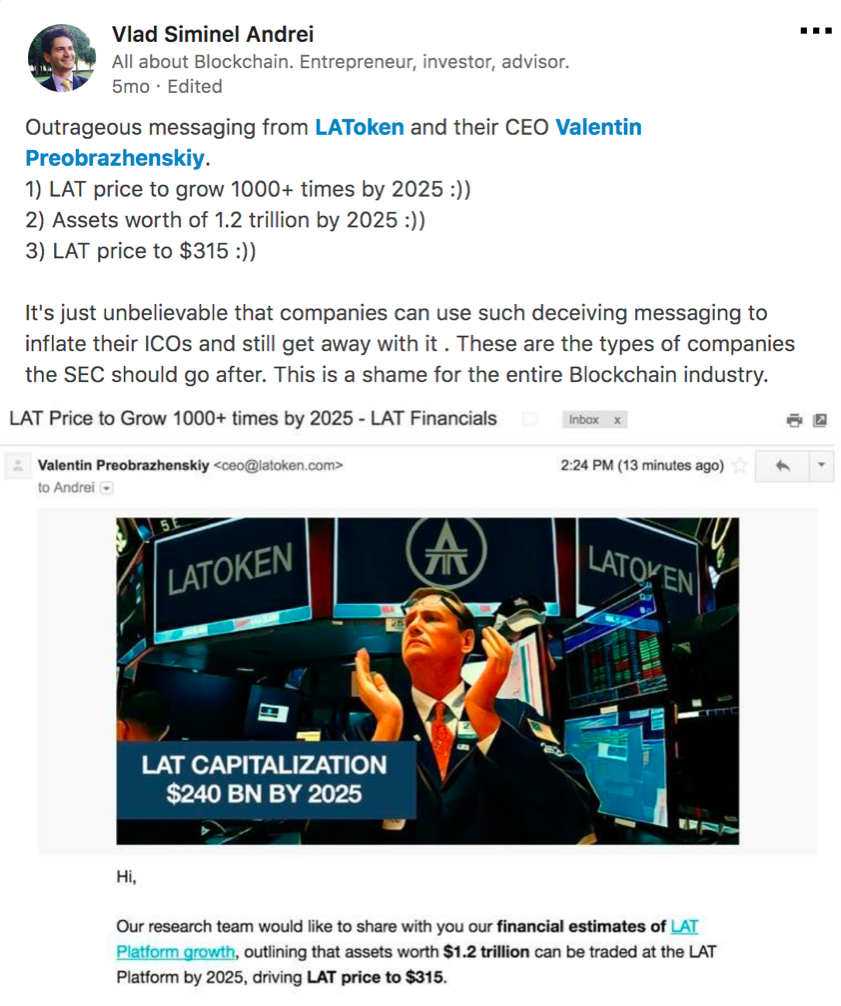

Additionally, ICO entrepreneurs over-promise what they can build and generally hype the potential speculative gains of their coin. They make false or misleading statements. The LAToken is particularly egregious, by saying they will build a token that can legally and effectively be backed by not just real estate, but also stocks, loans, commodities, and art. They also make several outlandish financial claims⁵:

Making false or misleading statements is one of the common charges brought by the SEC against ICO teams. For example,

The SEC filed charges against a recidivist Quebec securities law violator, Dominic Lacroix, and his company, PlexCorps. The Commission’s complaint, filed in federal court in Brooklyn, New York, alleges that Lacroix and PlexCorps marketed and sold securities called PlexCoin on the internet to investors in the U.S. and elsewhere, claiming that investments in PlexCoin would yield a 1,354 percent profit in less than 29 days.⁶

4) Token Distribution

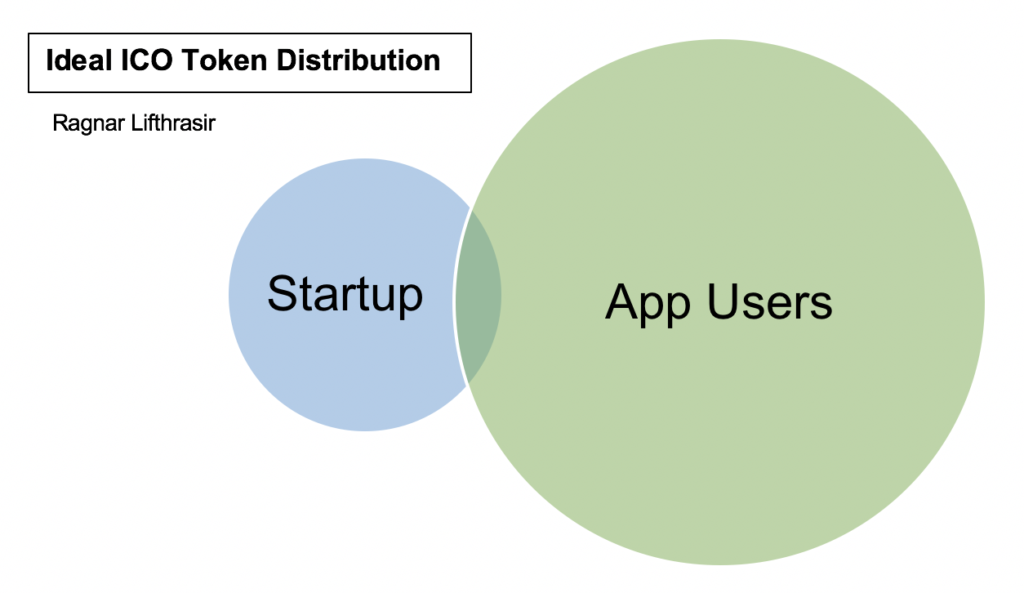

Tokens are supposed to get widely distributed among the future users of a blockchain application to drive a network effect. In an ideal token distribution, the app users have the majority of the tokens and they are widely distributed among millions or hundreds of millions of users.

However, in most ICO’s, the majority of tokens are bought up by VCs and professional investors (at a steep discount) in pre-sales and bought up by “whales” and sometimes front run by Ethereum miners in the first hours of the ICO. Often these large investors then later dump their tokens on retail investors on 3rd party exchanges.

The nature of the ICO puts most tokens in the hands of speculators, large and small, rather than in the hands of the actual users of the software. Although ICO’s have allowed non-accredited investors to access startups, most ICOs are still dominated by the professional investors, a marginal improvement over the traditional venture capital market. And at least traditional venture capital investors have equity claims and some voting rights.

5) Walls, Silos, and Friction

The plethora of third parties in real estate are sustained by moats of proprietary software or a data silo. Brokers make their commission off of their insider knowledge of the market. Title insurance companies hold a monopoly on title information. Only REALTORs have full access to the MLS databases.

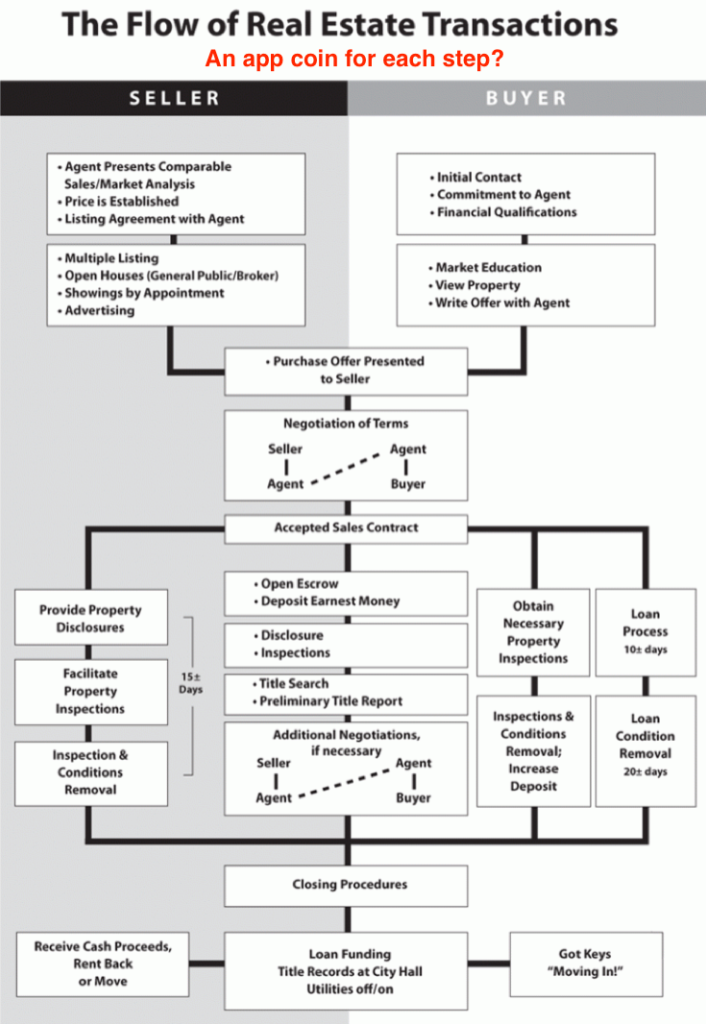

Each ICO becomes its own walled garden and data silo — a problem blockchain is supposed to solve. Some blockchain startups use an application specific blockchain token as a component of their software. For example, the Caviar project has their “CAV” token. These tokens are usually not needed for the software to accomplish its purpose, and in fact, creates an extra convenient step for users. The proprietary ICO tokens create software that is not interoperable with other blockchain real estate software.

One might have to use one token for a down payment, a different one for escrow, and another for title. Software users do not want to suffer this inconvenience that adds transactional friction — a problem blockchain is supposed to solve. Real estate involves heterogeneous stakeholders, performing different but ordered applications. As the number of application and company specific tokens proliferate, users will not want the inconvenience of using a separate token for each BRE application.

One of the harshest critics of appcoins (ICO tokens) is Daniel Krawisz, who wrote,

Appcoins are a terrible idea. And furthermore, this shouldn’t require such a deep analysis to realize. They are clearly just a needless complexity. Why would I want to use different money for my gas, food, and rent? This defeats the whole purpose of having a money economy. How can these appcoin proponents think they’re accomplishing something with that? It’s like they’re trying to invent a barter system again except improve it by adding trade barriers and a bunch of imaginary extra goods that aren’t useful for anything but that people are required to trade with for some reason.

In fact, it’s not like that. It’s exactly what they’re actually doing. Appcoins are pump-and-dump scams disguised as Rube Goldberg machines, so don’t get fooled.⁷

One company is proposing a token that can only be used by closed real estate consortium — the opposite of what the industry needs. Blockchain is meant to democratize and decentralize real estate. Legacy real estate firms who think they can control blockchain from disrupting them are the Blockbuster Videos of the world. R3 has tried a consortium, and is struggling, as, many predicted. Tim Swanson of R3 emailed me a few months back looking for guidance. The future is public blockchains, permissionless innovation, and merit based, open collaboration. A consortium is a way for incumbents to try to keep their power.

6) Advisor And Investor Weirdness

A few advisors, with their equity locked up and a clear scope of role can help startups with strategy, marketing, and other advisory help. However, the advisor role has been perverted with most ICO’s. In an attempt to add legitimacy to their project, many ICO’s have large number of advisors who often do nothing more than get paid for their name and do not offer long-term expertise. It’s greed on both sides, crypto window dressing. The practice has devolved to the point of ICO’s putting advisors on their white papers without the knowledge or consent of those individuals.

On November 1st, Forbes broke this story:

NextBlock Global, a venture capital company investing in digital assets that is going public in Canada and raising $100 million CAD ($77 million USD), falsely named four blockchain stars as advisors in an investor document.

The company’s chief executive officer, Alex Tapscott, is known for coauthoring, with his father Don, a book on blockchain technology, “Blockchain Revolution: How The Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business And The World,” which was a Globe and Mail bestseller.

An investor deck sent out by a broker via email Thursday, October 19, which touted its “access” and “unparalleled relationships” as its top selling point, listed eight advisors, including former U.S. Department of Justice prosecutor and current Coinbase Board of Directors member Kathryn Haun; serial blockchain entrepreneur Vinny Lingham, CEO of blockchain identity startup Civic and a shark on South Africa’s Shark Tank; Dmitry Buterin, father of Ethereum cofounder Vitalik Buterin; and Karen Gifford, a special advisor for global regulatory affairs at Ripple who was previously counsel and officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

“I’m not an advisor and I never have been,” Haun told Forbes.

“I’m not an advisor to his fund,” said Lingham by phone.

Buterin confirmed he had been approached to be an advisor but had declined.

Through a press representative, Gifford stated that she is not an advisor and that she never spoke with Tapscott about becoming one.⁸

Having fake advisors isn’t the only problem with ICOs. The incentive structure of ICO’s can make advisors and investors exercise poor judgement.

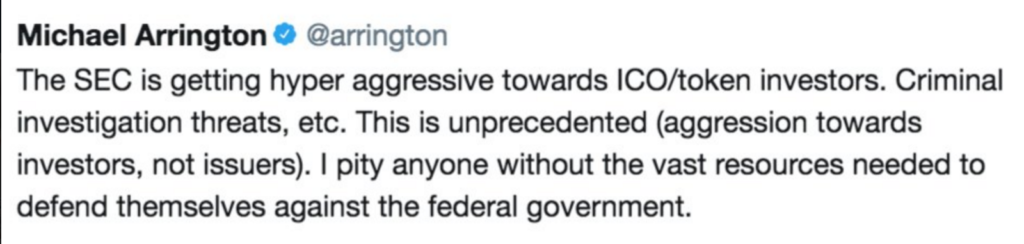

Michael Arrington, an advisor and investor to Propy, (he bought the first property on Propy) was personally subpoenaed as part of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s investigation of cryptocurrency offerings⁹. (It is not known for which of his ICO investments the subpoena was for). On February 17th Michael tweeted (and later deleted):

These tweets elicited several unsympathetic responses:

In a blog post, Gab explains what investors have been doing, and a likely reason for a wave of subpoenas¹⁰.

With this all said, what excuse did the hundreds of ICOs that launched in 2017 (and raised billions of dollars) have for not following securities laws? In such a new and exciting world for financing, you can probably cut some slack to some of the startup companies who may not fully understand the magnitude of what they were doing. Perhaps they trusted the wrong lawyer or made a foolish and naive mistake. It happens. What you can not excuse are the institutional Silicon Valley investors who knew exactly what they were doing and the massive amount of risk they were taking by promoting and investing in unregulated securities.

And

Let’s explain just exactly what these institutional investors were doing. The tweet above highlights the process beautifully. Silicon Valley elites were getting into ICOs months in advance with insanely discounted deals. They would then proceed to hype up the ICO for many months in advance. The ICO would go live, be listed on a few exchanges, and these Silicon Valley insiders would get a crazy return with very little work.

The dynamics and incentives of ICO has muddled the role and judgement of advisors and investors.

7) Security

The competency to create blockchain real estate software is not the same competency needed to securely perform an ICO. For example, within the first few hours of their ICO, REXmls lost 6,687 Ether (About $1,700,000 at the time) of investor funds by incorrectly coding their smart contract transfer address.¹¹ Even good teams are at risk due to various security issues with Ethereum token software:

According to Chainalysis, for the year 2017, fraudsters appropriated about 14% of the funds raised by projects using the Ethereum-based ICO, namely about $ 225 million out of $ 1.6 billion. As a result of fraudulent activity, about 30,000 investors suffered losses with an average of $7,500. Cybercrime in relation to investors’ financial resources is growing faster than the amount of investments attracted within ICO.¹²

8) Regulator Crackdown

Almost all ICOs violate US and other securities laws and are liable to future government crackdown.

It’s not just the SEC that is coming after ICOs, but also the CFTC, state agencies, and announced yesterday, FinCEN. From CoinDesk:

FinCEN released a letter to Senator Ron Wyden clearly indicating that they interpret the relevant laws and regulations such that token sellers are money transmitters:

“A developer that sells convertible virtual currency, including in the form of ICO coins or tokens, in exchange for another type of value that substitutes for currency is a money transmitter and must comply.”

Make no mistake, this is a highly consequential interpretation. Accordingly, any group or individual developer who both (A) sold newly created tokens to buyers (i.e. had an ICO) involving U.S. residents and (B) failed to register with FinCEN as a money transmitter,and perform the associated compliance KYC/AML obligations, can be charged under a federal felony criminal statute, 18 U.S.C § 1960, with unlicensed money transmission. If found guilty one could face up to five years in prison. Criminal liability may also extend to employees of, and investors in, the business that sold the tokens.¹³

This news should jar the proponents of ICOs for real estate.

The recent Caviar real estate ICO escaped the attention of the Federal SEC regulators but not of the state of Massachusetts regulators:

Just a month after launching an exam sweep of entities based in Massachusetts raising money from initial coin offerings, Commonwealth Secretary William Galvin on Wednesday charged a Brookline man and his company with the unregistered sale of a security marketed as “Caviar Tokens.”

According to the complaint, Kirill Bensonoff and his Cayman Islands company, Caviar, allegedly told Massachusetts investors that the proceeds from the Caviar Tokens would be used to fund house-flipping real estate projects, in addition to financing the acquisition of a portfolio of various cryptocurrencies.

“In sum and substance, Bensonoff and Caviar seek to use the proceeds of the ICO to finance the creation of a hedge fund and offer freely transferable shares to investors in the form of Caviar Tokens,” the complaint states. The complaint filed Wednesday by the Massachusetts Securities Division states that Caviar raised approximately $3.1 million through a combination of cryptocurrencies and cash.

“Bensonoff and Caviar have offered and continue to offer Caviar tokens without registration or exemption from registration in the Commonwealth,” Galvin said in a statement. Bensonoff formed Caviar in the Cayman Islands to avoid state securities regulation, Galvin says, but has conducted business out of his Brookline home.

“This serves as a warning to those who would try to use the recent Bitcoin craze to circumvent securities laws in Massachusetts,” Galvin added.

The Massachusetts Securities Division, he continued, “will be monitoring these cases closely, to ensure Massachusetts investors are not being taken advantage of by so-called ICO promoters trying to cash in on the latest get-rich-quick scam.”

While the company was prohibited from selling to American investors, advertisements for the so-called Caviar Tokens were targeted to Americans on various social media platforms, the complaint states. Also, until approximately Jan 4, 2018, the Caviar website “was generally accessible to any U.S. resident,” the complaint states. “Within 24 hours of appearing to provide testimony to the Enforcement Section, Bensonoff applied, or caused to be applied, a filter to exclude U.S.-based IP addresses from accessing the Caviar website.”

One of the internet ads referenced in the complaint stated that Caviar was “the hottest ICO of December” and promised offerees “Crypto and Real Estate in one TOKEN.” The complaint also alleges that Caviar failed to take appropriate measures to prevent Americans from investing in its product. In one such instance, a Massachusetts Securities Division investigator was able to participate in the token sale using the name of a popular cartoon character and a passport image obtained using a Google Image search.¹⁴

Over the past several months the SEC has escalated their intent to enforce securities laws on ICOs. The Chairman of the SEC, Jay Clayton, has made the strongest statements. In November,

Mr. Clayton went off script and stated that he has yet to see an ICO that doesn’t have “sufficient indicia” of being a securities offering. Mr. Clayton also commented that the trading platforms involved in the exchange of coins/tokens offered in ICOs could face SEC scrutiny and might have to either (i) register as national securities exchanges or (ii) make clear they have an exemption from doing so.¹⁵

Then on January 22nd, Chairman Clayton warned lawyers:

First, and most disturbing to me, there are ICOs where the lawyers involved appear to be, on the one hand, assisting promoters in structuring offerings of products that have many of the key features of a securities offering, but call it an “ICO,” which sounds pretty close to an “IPO.” On the other hand, those lawyers claim the products are not securities, and the promoters proceed without compliance with the securities laws, which deprives investors of the substantive and procedural investor protection requirements of our securities laws…

These lawyers appear to provide the “it depends” equivocal advice, rather than counseling their clients that the product they are promoting likely is a security,” added Clayton. “Their clients then proceed with the ICO without complying with the securities laws because those clients are willing to take the risk.¹⁶

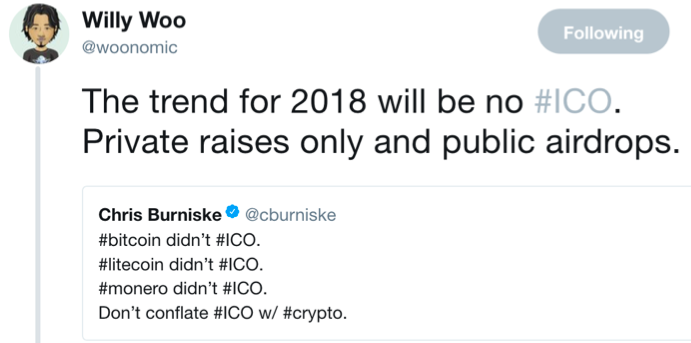

This change in enforcement has led to many predicting a significant slowdown of ICOs in 2018.

9) Class Action Lawsuits

Class action lawsuits might shut down more ICO projects than SEC enforcement actions. The non-compliance and legal structure of ICO’s make them more vulnerable to investor class action lawsuits. A recent example is the $232 million Tezos ICO:

The suit, filed by San Diego-based law firm Taylor-Copeland Law on behalf of plaintiff and Tezos ICO contributor Andrew Baker, alleges that the defendants violated U.S. securities law through the token sale. Specifically, the defendants are being accused of selling unregistered securities, committing securities fraud, false advertising and unfair competition (“by making material misrepresentations and omissions”).¹⁷

In December, a class action lawsuit was filed against the $30 million ICO Centra, popularly known for being promoted by Floyd Mayweather Jr.¹⁸ A couple of law firms have started ICO class action lawsuit practices, such as icoclassaction.com:

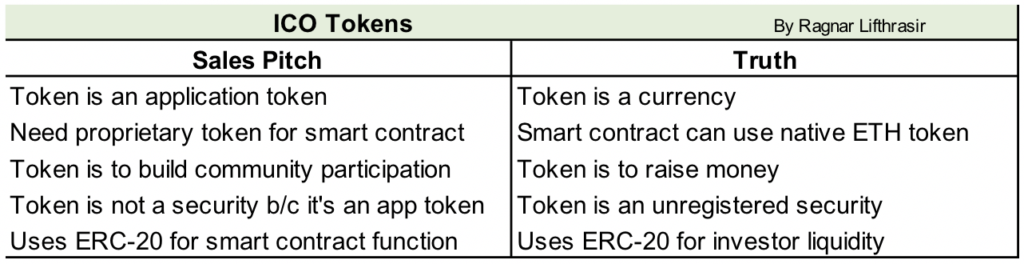

10) Token Dishonesty

ICO tokens are often dishonestly justified or mistakenly marketed.

The most common inaccuracy in token description is calling it an application token, for the intent of trying to avoid securities laws. However, even having functioning software does not necessarily mean a future token is an (exempt) application token as Munchee found out:

Within the SECs findings they noted that Munchee touted itself as a “utility” token which means that the company believed the MUN token would be primarily used within the Munchee ecosystem and not be used to fund operations. However, thanks to an application of the Howey Test (a Supreme Court finding that essentially states that any instrument with the expectation of return is an investment vehicle), the SEC found the Munchee was actually releasing a security masquerading as a utility.

“Munchee offered MUN tokens in order to raise capital to build a profitable enterprise,” read the SEC notice. “Munchee said that it would use the offering proceeds to run its business, including hiring people to develop its product, promoting the Munchee App, and ensuring ‘the smooth operation of the MUN token ecosystem.”¹⁹

ICO tokens present another risk, a technical one. Because the application token adds an unnecessary technical complexity to the software, a rival could recreate the software and make it better by removing the token and instead accept a more widely held cryptocurrency (such as bitcoin). Daniel Krawisz wrote,

Because any appcoin must compete with Bitcoin, there is inherently an aversion to holding the appcoin rather than Bitcoin. This means that an app can always improve by transitioning to use Bitcoin instead of the appcoin. Since we are talking about open source projects, it is always possible for anyone to fork an existing app and make the changes himself.²⁰

Returning to Daniel Krawisz again,²²

… whereas the value of a stock is related to the value of the company that issued it, there is no such connection between an appcoin and an app, and there is consequently no reason to expect the appcoin ever to become valuable. For this reason, appcoins should not be considered a valid investment and are inappropriate as a means of funding open-source projects.

And further,

…the value of an appcoin can move completely independently of the value of the app itself. This is because the value of a currency is due to the value of the network of people holding it, which is a logically separate concept to the network using the app. The value of the app is a matter entirely of the service it provides, whereas the value of the appcoin partly due to the value of the app and partly to its competition with other currencies. If there are two currencies to choose, there is a relative disutility of holding the one which has the smaller market cap.

Two Better Alternatives To ICOs

There are two better ways for startups to raise capital.

- Security Token + Cryptocurrency/ rewards Token

A coin to raise capital should function as a stock, not try to be a functional part of the software stack or be a proprietary currency. Some call this a Security Token Offering (SCO) or Tokenized Asset Offerings (TAO). These tokens will be traded on a licensed Alternative Trading System (ATS).

…the capital markets arm of Overstock’s blockchain-focused subsidiary Medici, is launching a first-of-its-kind alternative trading system (ATS) that will provide a platform for the exchange of cryptographic tokens categorized in the U.S. as securities.

A joint venture with RenGen (a fintech firm that will serve as the market maker) and Argon Group (an investment bank specializing in ICO capital raising), the ATS will be regulated by both the SEC and the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

In short, the ATS will offer a legally approved, regulated alternative to a major securities exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq.²¹

In addition to the tZERO exchange, there are other exchanges in the works including Templum, Polymath, Prometheum, and others.

A separate coin should serve as a cryptocurrency with an access / rewards functionality, preferably one held by the greatest number of people, as that is what gives currency its value/utility. This is not a security. It’s a (crypto)currency like bitcoin or a new one created to serve a similar purpose.

2. Non-token Crowdfunding

Blockchain real estate startups don’t need to use a token to raise capital with crowdfunding. For example, balance.io is an Ethereum wallet that supports all ERC-20 and ERC-721 tokens. Last year they used WeFunder to raise $1,170,000 from 1614 investors in exchange for equity. Balance published a blog post titled, “Why We Are Not Doing A Billion Dollar ICO We are doing an Initial Crowd Offering. Crowd, not coin.” An excerpt:

We are building a product, not a protocol

We are focused on creating the best interface for digital currencies and tokens. It is a big project but it is not a protocol. We do not want to create a token and issue it for no good reason.

If we create a token, we want it to have real value.

There may come a time in the future where we launch a useful protocol with a valuable token. We are not doing that now. We want to create a company that creates products for protocols. To help do that, we are raising money through crowdfunding.

Summary

The fallout from these ten problems with ICO’s has barely begun. Once these startups fail to deliver on all of their promises and they lose money from the token dropping in value, some investors will seek compensation via a class action law suit. The SEC will begin more frequent and more aggressive enforcement actions.

Users of these blockchain real estate applications will become frustrated with having to secure and use different tokens for different uses. Some ICOs have lock up periods for investors, as those expire, they will sell their tokens creating downward pressure on token value, decreasing the capital available to startup founders to fund their operations. The net result will be a downward spiral in token value. Conservative, traditional real estate companies read about the ICO scams and hacks and conflate it with all blockchain, and decide to wait on adopting blockchain or buying cryptocurrency.

The solution is to raise capital with a regulatory compliant security token or a non-token crowdfunding campaign. A cryptocurrency or non-security token can be used by startups to incentivize, and get paid for, various actions. Better blockchain real estate startups will be produced in 2018 by ditching non-compliant ICOs.

Click here to learn more about author Ragnar Lifthrasir on his personal website

Featured image source: Getty Images – tampatra