Today, approximately 330 million households worldwide do not have access to adequate and affordable housing. (see Harvard Business Review) In many countries around the world, the story is the same: too much demand and not enough supply. Demand constraints are most often driven by a lack of debt financing. Emerging economies, without significant mortgage access, account for only 5% of housing ownership. (See The World Bank). Supply constraints, on the other hand, are related to regulatory and planning restrictions that drive up the costs of land or make development nearly impossible. As populations continue to grow, the challenge to bridge the gap of what is supplied versus what is affordable is becoming that much larger. A projected 3 billion people (40% of the world’s population) will not be able to afford housing by 2030 without some drastic changes in housing access.

Today, approximately 330 million households worldwide do not have access to adequate and affordable housing. (see Harvard Business Review) In many countries around the world, the story is the same: too much demand and not enough supply. Demand constraints are most often driven by a lack of debt financing. Emerging economies, without significant mortgage access, account for only 5% of housing ownership. (See The World Bank). Supply constraints, on the other hand, are related to regulatory and planning restrictions that drive up the costs of land or make development nearly impossible. As populations continue to grow, the challenge to bridge the gap of what is supplied versus what is affordable is becoming that much larger. A projected 3 billion people (40% of the world’s population) will not be able to afford housing by 2030 without some drastic changes in housing access.

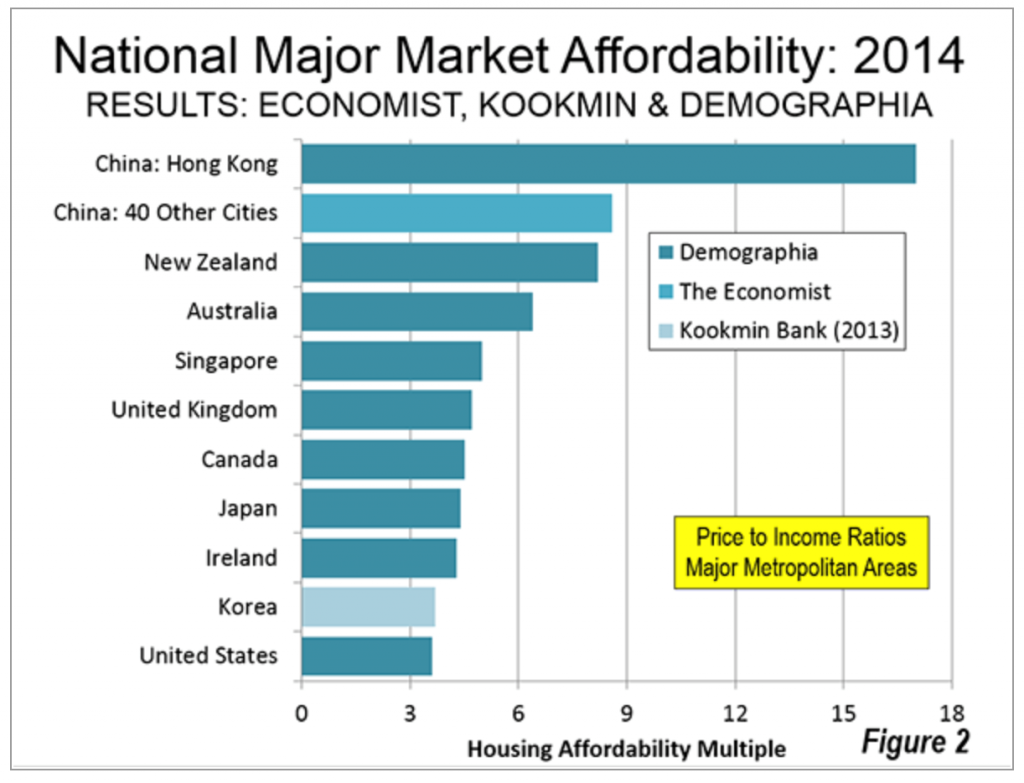

The 11th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey ranked nations in all major markets on housing affordability based on the median multiple (median house price divided by gross annual median household income) and found that the US was the most affordable nation in the world, with a median multiple of 3.4. Unsurprisingly, the least affordable nation in the world is China (Hong Kong) with a median multiple of 17.0, the highest ever recorded. (New Geography) Although the US is ranked the most affordable country, especially if you don’t mind living in Detroit, Rochester, Buffalo or Cleveland, other markets were rated as being severely unaffordable: San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego, Los Angeles, New York, Miami, and Boston, to name a few. New York, which has the largest public housing authority in North America, has not been able to put a dent in the demand for less expensive housing. Strict eligibility requirements have resulted in public housing tenants at the low end of the socioeconomic scale with an average household income of $23,150. The current waiting list for housing exceeds the number of households being served (Shareable). New York may be an extreme case, but in the other unaffordable markets in the US, restrictive land use regulation and urban containment policies add to the price of housing. San Francisco has many residents trying to put a moratorium on new housing in order to mitigate traffic and infrastructure concerns, and they are not unusual (Demographia). Just the opposite is needed in order to provide more market rate housing that is affordable: greater density.

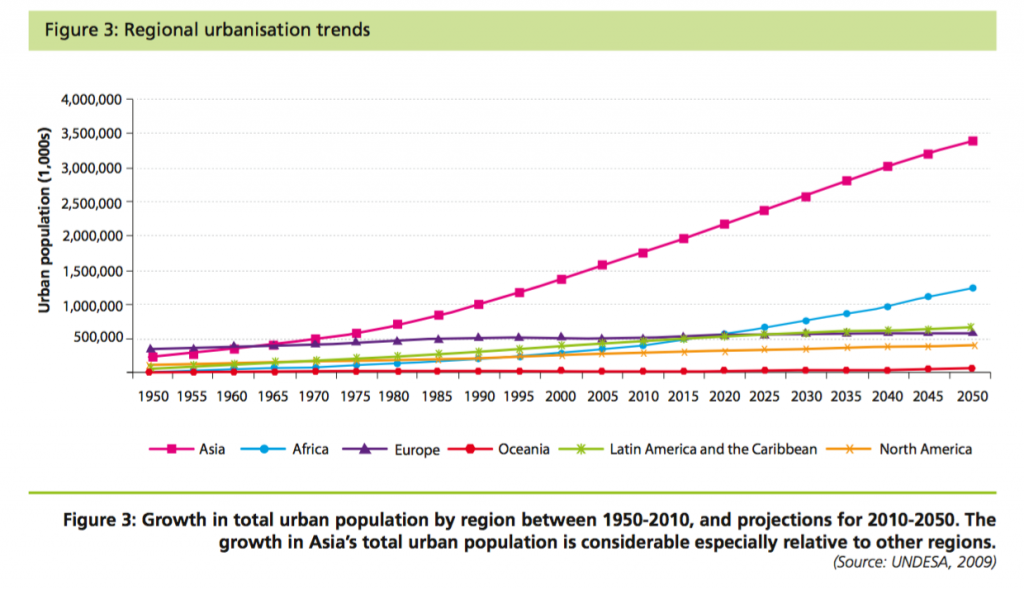

Although the US is ranked the most affordable country, especially if you don’t mind living in Detroit, Rochester, Buffalo or Cleveland, other markets were rated as being severely unaffordable: San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego, Los Angeles, New York, Miami, and Boston, to name a few. New York, which has the largest public housing authority in North America, has not been able to put a dent in the demand for less expensive housing. Strict eligibility requirements have resulted in public housing tenants at the low end of the socioeconomic scale with an average household income of $23,150. The current waiting list for housing exceeds the number of households being served (Shareable). New York may be an extreme case, but in the other unaffordable markets in the US, restrictive land use regulation and urban containment policies add to the price of housing. San Francisco has many residents trying to put a moratorium on new housing in order to mitigate traffic and infrastructure concerns, and they are not unusual (Demographia). Just the opposite is needed in order to provide more market rate housing that is affordable: greater density. Meanwhile, Asia is projected to experience the fastest urban growth in the coming decades. Southern Asia in particular is expected to double its urban population by 2050 (Unhabitat: Affordable Land and Housing in Asia). The lack of affordable housing in Hong Kong, for example, has been perpetuated by the fact that 48% of residential transactions were more than HK$5 million, while median incomes have stagnated. Housing costs divided by median incomes rose 220% between 2003 and 2013 (Demographia). With waiting lists at an all-time high, the government’s target is to build 470,000 affordable units within the next 10 years, 60% of which will be allocated as affordable. In order to do this, the government is considering several options which include lifting height restrictions on new development, offering incentives to increase private sector participation, and allowing for flexibility in zoning and planning to streamline implementation and housing delivery (Urban Land Institute). Again, the key is to allow greater density.

Meanwhile, Asia is projected to experience the fastest urban growth in the coming decades. Southern Asia in particular is expected to double its urban population by 2050 (Unhabitat: Affordable Land and Housing in Asia). The lack of affordable housing in Hong Kong, for example, has been perpetuated by the fact that 48% of residential transactions were more than HK$5 million, while median incomes have stagnated. Housing costs divided by median incomes rose 220% between 2003 and 2013 (Demographia). With waiting lists at an all-time high, the government’s target is to build 470,000 affordable units within the next 10 years, 60% of which will be allocated as affordable. In order to do this, the government is considering several options which include lifting height restrictions on new development, offering incentives to increase private sector participation, and allowing for flexibility in zoning and planning to streamline implementation and housing delivery (Urban Land Institute). Again, the key is to allow greater density.

In other regions of the world, the lack of affordable housing and efforts to mitigate the situation vary in scale:

| Europe | · The most affordable nations are Denmark, Austria and France

· The United Kingdom is severely unaffordable due to urban containment policies. · In Sweden, Greece and the Netherlands, social housing reforms put strict income guidelines on eligibility · The Tenlaw Project has been initiated to regulate rental housing including rent control and security of tenure (The State of Housing in the EU 2015) |

| Latin America | · Countries like Argentina and Mexico are making strides in creating affordable housing opportunities

· Brazil has ramped up production of affordable housing creating 2.2 million housing units since 2009 (The City Fix) |

| Africa | · 2.2 million households live in informal settlements or backyard shacks in South Africa while they wait for public housing which can take up to 25 years

· Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have successfully reduced slum populations from 20.8 million to 11.8 million between 1990-2010 (Affordable Land and Housing in Africa) |

In the midst of all the affordable housing challenges in various parts of the world, possibly the most effective models can be found in Vienna, Austria and Singapore. In Vienna, 60% of residents live in public housing. Christoph Reinprecht summarises the Austrian approach to social housing as follows: « There is a general political consensus that society should be responsible for housing supply, and that housing is a basic human need that should not be subject to free market mechanisms; rather, society should ensure that a sufficient number of dwellings are available » (Shareable). Because of this view, public housing in Vienna is mostly financed by public funds. And, as opposed to subsidizing rents, subsidies are applied to construction costs. Since most of the housing stock is publicly owned, landlords compete for the same tenants and therefore cannot afford to inflate rents.

Singapore, on the other hand, encourages its citizens to purchase public housing units. 82% of residents live in units built by Singapore’s Housing Development Board (HDB). Nine out of ten HDB residents own their homes. Instead of dispersing subsidies, Singapore offers grants and awards up to S$60,000 to first time homebuyers and allows buyers to tap into their Central Provident Fund savings (Singapore’s social security system) for down payments and monthly mortgage installments. So, in many cases, no outlay of cash is required to purchase a home. Additionally, approximately 50,000 units are reserved for the truly needy, where residents can pay as little as $20/per month for rent. One perceived weakness of Singapore’s program, however, is that HDB oversees control of every aspect of the system including building, selling and lending for all built units (Shareable).

Social housing programmes are not always viewed optimistically, but at their core, they treat adequate and affordable housing as a basic right. In capitalistic societies, affordable housing is often viewed as a privilege.

Social housing programmes are not always viewed optimistically, but at their core, they treat adequate and affordable housing as a basic right. In capitalistic societies, affordable housing is often viewed as a privilege.

Regardless of your stance on the subject, it is undeniable that housing affordability is taking centre stage as it impacts economies across the globe. As various models and approaches are being employed worldwide to address anticipated population growth over the coming years, it is evident that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this mounting dilemma.